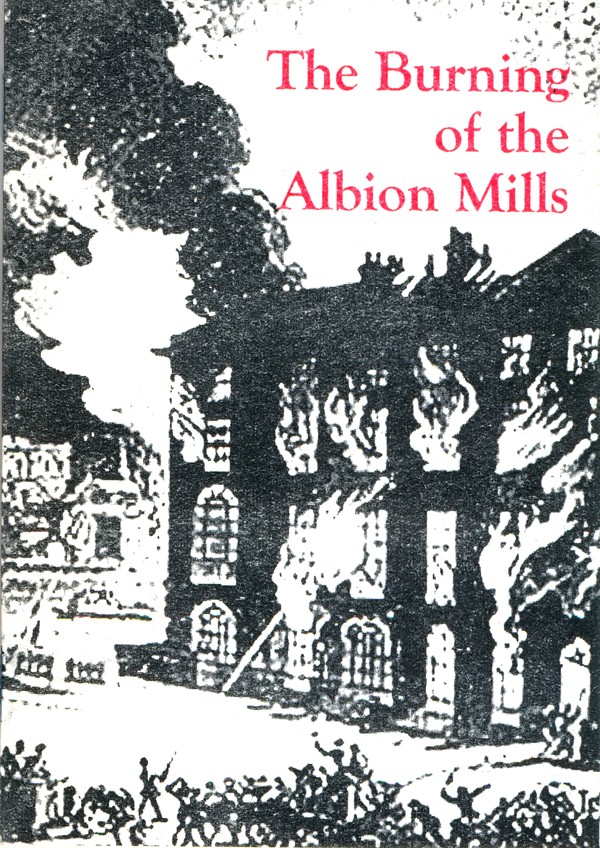

The Burning of Albion Mills

£1.00

Was it arson? The Mills stood in Blackfriars, an area together with neighbouring Southwark long notorious for its rebellious poor and for artisan and early working class political organization. …….. did workers displaced orfearing displacement by the Mills take matters into their own hands?

In stock

Description

The new A5 version of this pamphlet with a colour cover!

The Albion Mills, the first great factory in London, formerly stood on the east side of Blackfriars Road, on the approach to Blackfriars Bridge. They were steam-powered mills, established in 1786 by Matthew Boulton & James Watt, featuring one of the first uses of Watt’s steam engines to drive machinery, and were designed by pioneering engineer John Rennie (who later built nearby London Bridge). Grinding 10 bushels of wheat per hour, by 20 pairs of 150 horsepower millstones, the Mills were the ‘Industrial wonder’ of the time, quickly becoming a fashionable sight of the London scene… Erasmus Darwin called them “the most powerful machines in the world.”

But if the trendy middle and upper classes liked to drive to Blackfriars in their coaches and gawp at the new industrial age being born, other, harder eyes saw Albion Mills in different light. They were widely resented, especially by local millers and millworkers…

At one time the Thames bank at Lambeth was littered with windmills – eventually they were all put out of business by steam power. When the Albion opened London millers feared ruin.

Steam was one of the major driving forces of industrialization and the growth of capitalism. The spectre of mechanization, of labour being herded together in larger and larger factories, was beginning to bite. Already artisan and skilled trades were starting to decline, agricultural workers were being forced into cities to find work, dispossessed from the countryside by enclosure and farm machinery… Many of those who had not yet felt the hand of factory production driving down wages, deskilling, alienating and shortening the lifespan, could read the writing on the wall.

Mills & millers were often the focus of popular anger. Not only were they widely believed to practice forms of adulteration, adding all sorts of rubbish to flour to increase profits (Significantly in many folk and fairy tales the miller is often a greedy cheating baddie), but at times of high wheat prices and thus, (since bread was the main diet of the poor) widespread hunger, bakers and millers would be the target of rioters, often accused along with farmers and landowners of hoarding to jack up prices. Bread riots could involve the whole community, though they were often led by women. Rioters would often seize bread and force bakers to it at a price they thought fair, or a long-established price; this was the strongest example of the so-called ‘moral economy’ (discussed by EP Thompson and other radical

historians) a set of economic and social practices based in a popular view of how certain basic needs ought to be fairly and cheaply available.

The idea of a moral economy was one that crossed class boundaries, a reflection of the paternalist society, where all knew their place, but all classes had responsibilities and there were certain given rights to survival. But this moral economy, such as it was, was bound up with pre-capitalist society – which were being superseded by the growth of

capitalism, of social relations based solely on profit and wage labour…