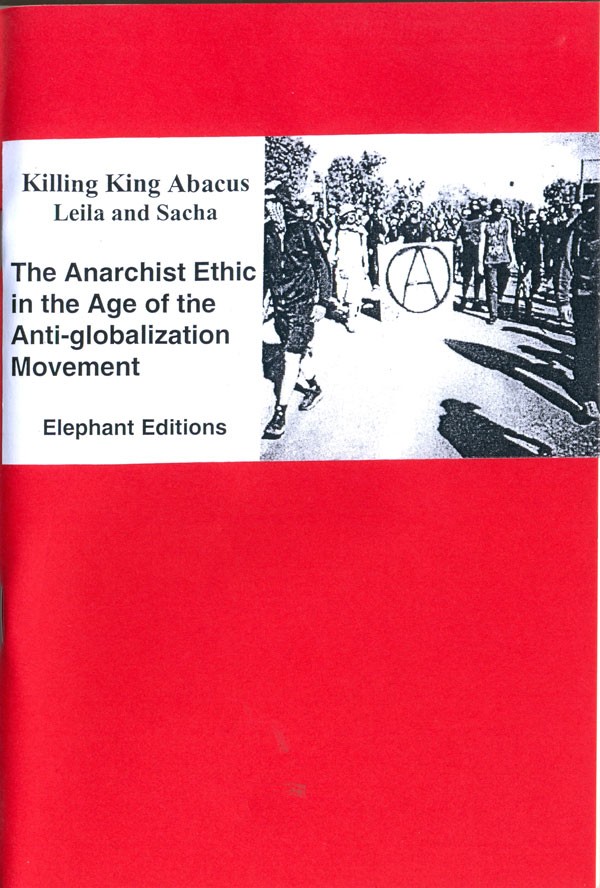

The Anarchist Ethic in the Age of the Anti-globalisation Movement Leila and Sacha

£1.20

Reprints of writings critiquing the Anti-Globalization Movement, Ya Basta ,Genoa and the Black Block.

In stock

Description

The question always before anarchists is how to act in the present moment of struggle against capitalism and the state. As new forms of social struggles are becoming more clearly understood, this question becomes even more important. In order to answer these questions we have to clarify the relationship between anarchists and the wider social movement of the exploited and the nature of that movement itself. First of all, we need to note that the movement of the exploited is always in course. There is no use in anarchists, who wish to destroy capitalism and the state in their entirety, waiting to act on some future date, as predicted by an objectivist reading of capitalism or a determinist understanding of history as if one were reading the stars. This is the most secure way of keeping us locked in the present forever. The revolutionary movement of the exploited multitude never totally disappears, no matter how hidden it is. Above all this is a movement to destroy the separation between us, the exploited, and our conditions of existence, that which we need to live. It is a movement of society against the state. We can see this movement, however incoherent or unconscious, in the actions of Brazil’s peasants who take the land they need to survive, when the poor steal, or when someone attacks the state that maintains the system of exclusion and exploitation. We can see this movement in the actions of those who attack the machinery that destroys our very life-giving environment. Within this current, anarchists are a minority. And, as conscious anarchists, we don’t stand outside the movement, propagandizing and organizing it; we act with this current, helping to reanimate and sharpen its struggles.

It is instructive to look back at the recent history of this current. In the U.S., beginning in the 1970s, social movements began to fracture into single-issue struggles that left the totality of social relations unchallenged. In many ways, this was reflected in a shift in the form of imposed social relations, which occurred in response to the struggles of the 1960s and early 1970, and is marked by a shift from a Fordist regime of accumulation (dominated by large factories and a mediated truce with unions) to a regime of flexible accumulation (which began to break unions, dismantle the welfare state, and open borders to the free flow of capital). This shift is also mirrored by the academic shift to postmodernist theory, which privileges the fractured, the floating, and the flexible. While the growth of single-issue groups signals the defeat of the anti-capitalist struggles of the 1960s, over the 1990s we have witnessed a reconvergence of struggles that are beginning to challenge capitalism as a totality. Thus the revolutionary current of the exploited and excluded has recently reemerged in a cycle of confrontations that began in the third world and have spread to the first world of London, Seattle, and Prague, and in the direct action movement that has, for the most part, grown out of the radical environmental milieu. In the spectacular confrontations of the global days of action1, these streams have been converging into a powerful social force. The key to this reconvergence is that the new struggles of the 1990s are creating ways to communicate and link local and particular struggles without building stifling organizations that attempt to synthesize all struggle under their command. Fundamental to this movement is an ethic that stands against all that separates us from our conditions of existence and all that separates us from our power to transform the world and to create social relations beyond measure—a measure imposed from above. This ethic is a call for the self-organization of freedom, the self-valorization of human activity.

In this article we will outline our understanding of the ethic of the revolutionary anarchist current of society that grows out of the movement of the exploited in general. Then we will turn to the question of action and organization, looking critically at the forms of struggle that are appearing in the recent cycle of social movements and arguing that informal organization is the best way for anarchists to organize as a minority within the wider social movement. By organizing along these lines, we believe anarchists can sharpen the level of struggle and develop social relations in practice that are both antagonistic to capital and the state and begin to create of new ways of living.