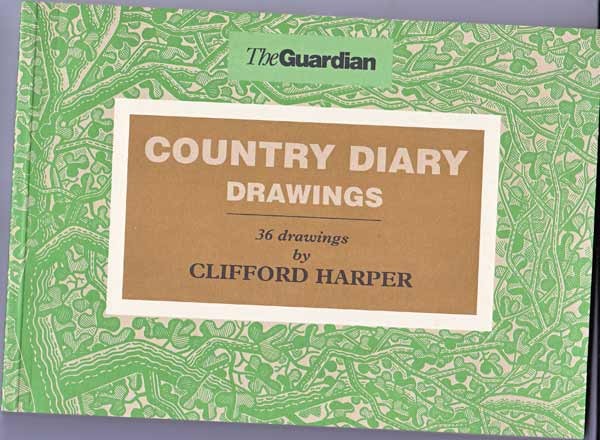

Country Diary Drawings

£6.76

36 illustrations from the anarchist illustrator, together with an introduction from the writer Richard Boston.

Description

From the Guardian…

Clifford Harper’s grandfather, father, uncles and brother were all postmen. A few years ago, he made his personal contribution to the Royal Mail by producing his own postage stamps. Intended for post-revolutionary post, these designs for anarchist stamps did not bear the usual portraits of heads of state, but of its enemies – anarchists and sort-of anarchists, such as the Digger Gerrard Winstanley, and William Godwin, Shelley, Proudhon (“property is theft”), Bakunin, Kropotkin, Oscar Wilde, Emma Goldman and Emiliano Zapata.

Harper’s distinctive bold black-and-white work combines the 19th-century French revolutionary tradition – including the work of anarchist Felix Vallotton – with an English one of woodcuts and wood-engravings that includes Walter Crane, William Morris and Eric Gill and that, indeed, goes back to the great Thomas Bewick himself.

Woodcuts are made using the side grain, often of apple wood. Wood-engravers use the end grain of an extremely hard wood, usually box wood or yew. Woodcuts have an attractive freedom about them, similar to that of the less durable lino-cut. Wood-engravings can use a much finer line, with effects that are more subtle. Which does Harper use?

The slightly surprising answer is that he doesn’t use wood at all; nor does he make prints. He is self-taught and, anarchist that he is, has come up with something of his very own. He draws on CS1O Line Board with black ink and a Rotring Rapidograph pen with either an .01 or .03 nib. Lines and cross-hatching are scratched into the black with an Edding scalpel. The result is finer than scraper-board (a most unsympathetic medium, in my view) and is made finer still by being reduced in reproduction; Harper usually works about one-third up on what will be the finished work. So, in the end, it is a printed work after all. It’s just that in this case the printing is not done by the artist but by the newspaper or magazine for which it has been executed.

The purist may have reservations about something that looks like a wood-engraving but isn’t. My own view is that anything goes. If it works for the artist then it works. Anyway, nobody who has done any wood-engraving would be mistaken for long. The cross-hatching is one give-away. When he cuts the wood the engraver makes a white line. The illusion of tone is made by cross-hatching white lines on a black background. Harper’s cross-hatching is often black on white; therefore it’s been done with a pen.

This actually extends the vocabulary available to Harper, in that he can do two different kinds of cross-hatching. This does something to make up for what I feel he has lost in the various effects (of stippling, for example) available to the engraver. There is, too, a supple life in the engraver’s line, the unique result of controlled manual effort, that is as special as the calligraphy of fine penmanship. But perhaps we’re in danger of getting into connoisseurship here, and I don’t think that’s what Harper is after. What is important is that his drawings work on the page, and in practice they work very well and in a variety of forms.

Vallotton’s woodcuts were just an episode in his extraordinarily productive and versatile career. Their narrative style was further developed by the Belgian artist Frans Masereel (1889-1972), who in the 1920s produced entire novels without words, just black-and-white images. Harper has produced a powerful little book in this genre about a first world war deserter shot for cowardice ( The Unknown Deserter, Working Press). In addition, there has been his book of stamps and numerous other publications, but most of his work has appeared in fairly obscure underground publications with tiny circulations. It is all the more heartening that in the past few years his work has been reaching a very much wider audience, especially through the Guardian.

His 31 drawings for the Guardian’s Country Diary were immediately and deservedly popular. The Country Diary has to tread a careful path if it is not to fall into the kind of prose that Evelyn Waugh parodied with such deadly accuracy in Scoop. “Feather-footed through the plashy fen passes the questing vole,” writes William Boot in his “Lush Places” nature notes for The Beast. For the most part the Guardian country diarists avoid the Boot-trap, though I confess to taking a perverse pleasure in sometimes spotting descriptive prose in which the writer has accidentally and unconsciously fallen into blank verse.

Harper’s vignettes are tough enough to be a useful corrective to any tendency to romanticised lushness. Individually they continue to give pleasure, however often they appear in the paper. The effect of seeing them not day by day but all together, is different. They seem to be telling a story the way Masereel’s do. The setting is a harsh countryside. Much of the time it is night, as evidenced by stars, the moon, car-headlights and nocturnal animals, such as the badger. It is usually winter, as is shown by leafless trees or snow. It is not the rural Britain of today with its foot-and-mouth and BSE and vast combine harvesters and huge cylindrical straw bales. We know this because there’s a horse-drawn plough, a sight that’s been rare for three-quarters of a century. But there are also huge cooling towers and a motorway. That’s odd – there’s no traffic on the motorway, not a single car, and the village street is deserted. There’s a badger and a fish and a frog and quite a few birds, but no cattle, pigs or poultry and the only sheep is a lamb that looks as though it is for a church window rather than a butcher’s. And where have all the people gone? It’s not just a deserted village but a whole countryside that’s depopulated. There’s a man and a woman, and a brief moment of what might be joy as they glimpse a boat that might offer the chance of freedom, of flight like that of the bird in the sky. But when the boat sails it looks as though only one of them is in it. The solitary man seems depressed, while the solitary woman looks as though she may quite enjoy just lying on the grass with a book. It’s all a bit mysterious, a bit unsettling, a bit uncomfortable.

The Country Diary drawings are intended to be seen one at a time, as they appear in the newspaper – and on newsprint, not art paper. By collecting them together they acquire (for me, at least) a narrative quality. They are also changed on seeing them on a different kind of paper, and not surrounded by columns of type but framed on a blank wall or in a book. The context makes a huge difference, and another context is the rest of Harper’s work. I have referred to some of this already but mention should be made of other drawings on a rural theme – for example, the self-sufficiency drawings he did years ago for the book Radical Technology, or the more recent vignettes for Country Life magazine. Then over the last three years or so there have been the illustrations for AC Grayling’s Last Word column and James Fenton’s weekly contributions to the Saturday Guardian. These are bigger in scale and (I get the impression) are making more use of tone.

Harper’s work is changing and developing. He sent me a gloriously bucolic roistering Christmas/New Year card, the high spirits of which balance his illustrations for James Thomson’s dystopian poem “The City of Dreadful Night” ( Agraphia Press, 2003). There will be, I am sure, much else. His work is varied and rewards attention, and the Country Diary drawings are a good place to start.

Additional information

| Weight | 0.345000 kg |

|---|